In our experience, we have seen many organizations working on the fruit and not the important components that produce the fruit.

We are privileged to work with many agriculturally based companies and often rub shoulders with the people who feed us on a daily basis. From that experience, we know that if you ask a farmer, he will tell you that when the fruit is mature, there isn’t much you can do to make it better. You might be able to shine it up a little on your sleeve, but if it’s bad, you’ve just drawn attention to the badness.

The same holds true for what you are selling/promoting (the fruit). Focusing your efforts on the final product and ignoring your brand is an exercise in fruitility (pun intended) and disappointment.

Nature teaches us, along with many other scenarios, that we must look after the plant in order to realize great fruit. We must carefully look after (nurture, empower and protect) the brand, which will then produce the desired results.

We’ve all heard the saying money doesn’t grow on trees. Often, that’s because we haven’t looked after our tree the way we should have.

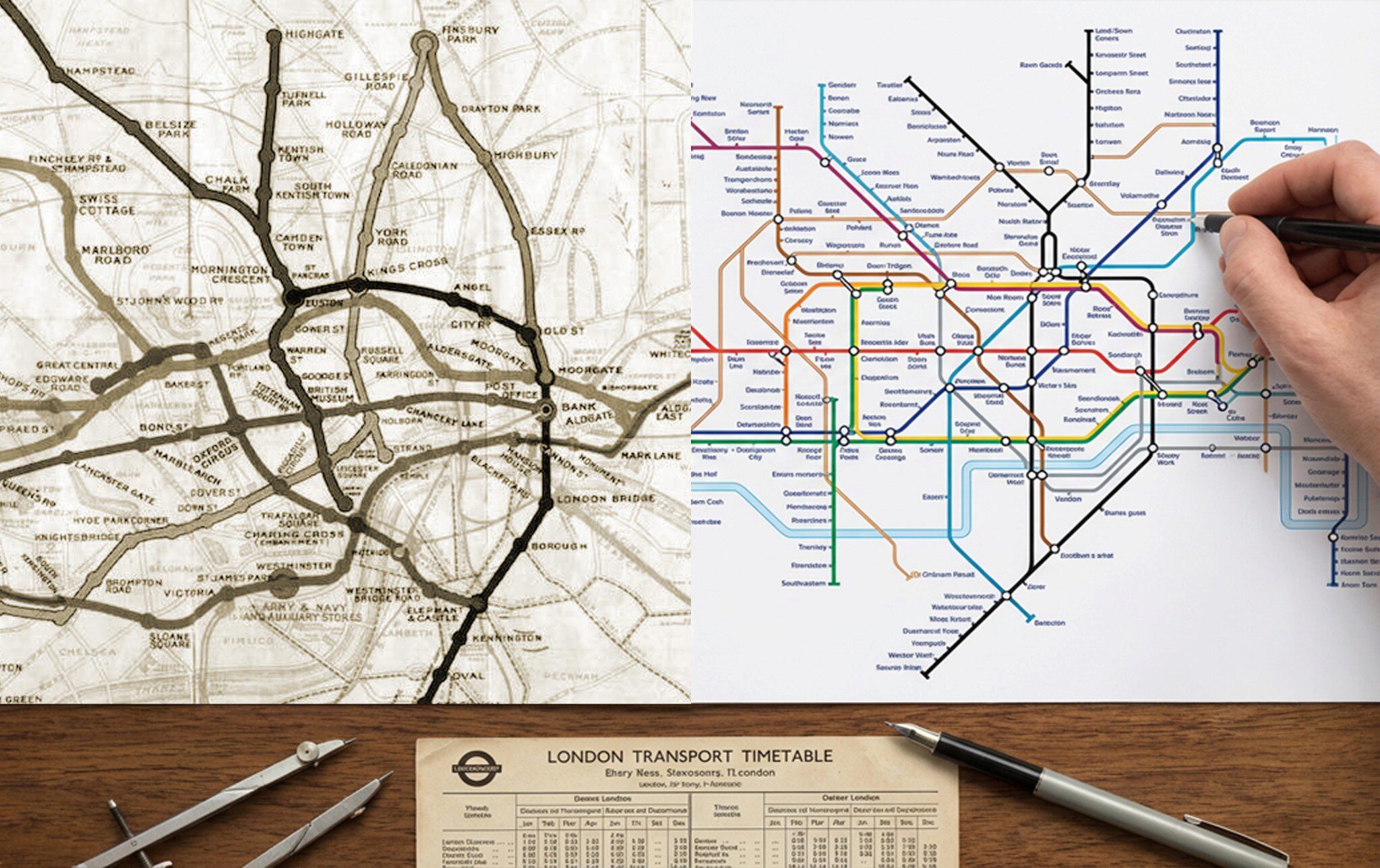

In 1933, commuters in London were drowning in information. The city’s underground railway had grown rapidly, and official maps tried to show every tunnel exactly as it existed underground. Lines curved and twisted to match geography. Distances were technically accurate. Streets, rivers and landmarks crowded the page. The result was a mess. Riders squinted, hesitated and missed their stops — not because the system was broken, but because the message was.

For most of history, grocery shopping looked nothing like it does today. You walked into a store, handed a list to a clerk and waited. The clerk fetched flour from one barrel, sugar from another and canned goods from shelves you never touched. Shopping was efficient, but it was also invisible. Customers didn't browse. They didn't linger. They didn't discover.

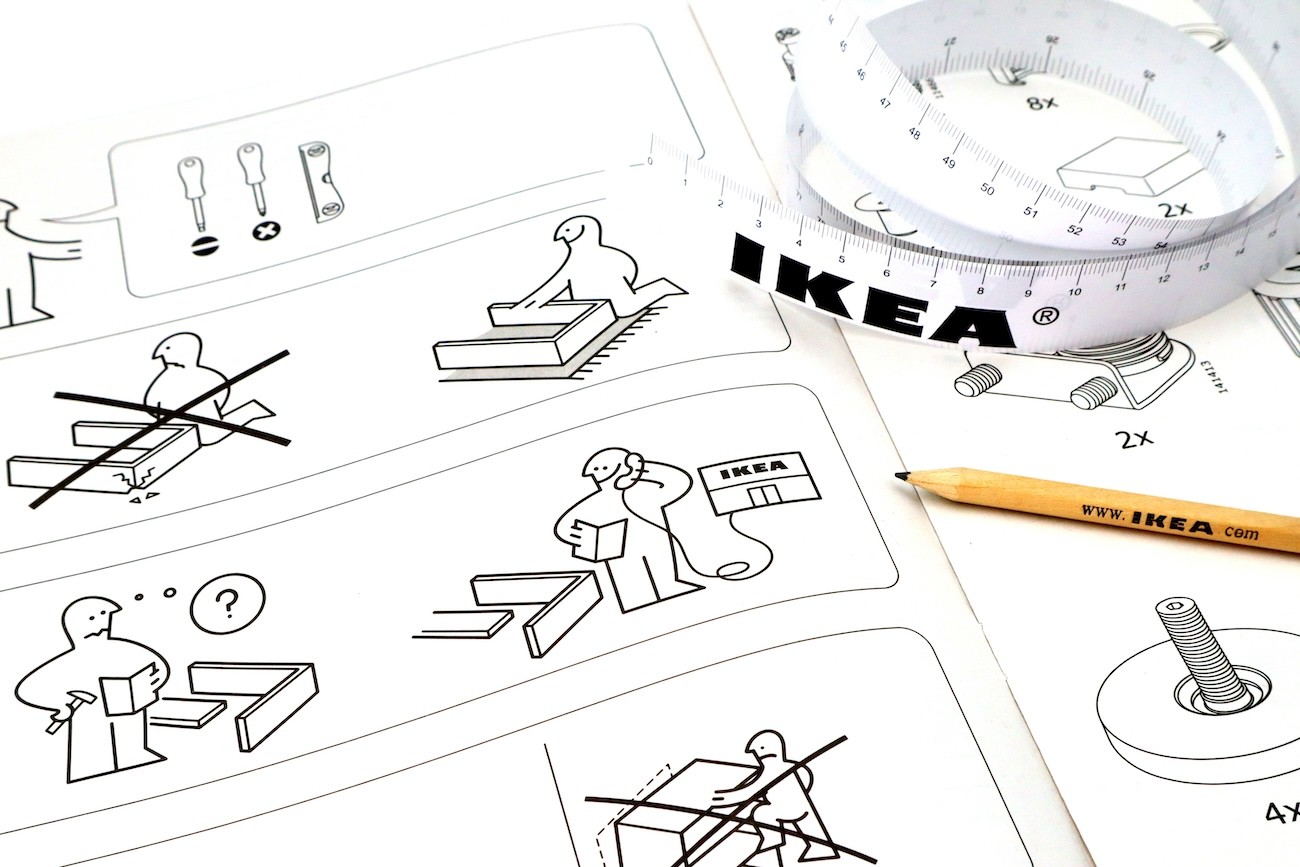

If you’ve ever built a piece of IKEA furniture, you know the moment. You open the box, spread the parts across the floor and stare at a small paper booklet filled with tiny drawings. No words or explanations; just arrows, dots and the suggestion that this should all make sense.